Hydropower

Hydropower, hydraulic power, hydrokinetic power or water power is power that is derived from the force or energy of falling water, which may be harnessed for useful purposes. Since ancient times, hydropower has been used for irrigation and the operation of various mechanical devices, such as watermills, sawmills, textile mills, dock cranes, and domestic lifts. Since the early 20th century, the term is used almost exclusively in conjunction with the modern development of hydro-electric power, the energy of which could be transmitted considerable distance between where it was created to where it was consumed.

Another previous method used to transmit energy had employed a trompe, which produces compressed air from falling water, that could then be piped to power other machinery at a distance from the energy source.

Water's power is manifested in hydrology, by the forces of water on the riverbed and banks of a river. When a river is in flood, it is at its most powerful, and moves the greatest amount of sediment. This higher force results in the removal of sediment and other material from the riverbed and banks of the river, locally causing erosion, transport and, with lower flow, sedimentation downstream.

Contents |

History

Early uses of waterpower date back to Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, where irrigation has been used since the 6th millennium BC and water clocks had been used since the early 2nd millennium BC. Other early examples of water power include the Qanat system in ancient Persia and the Turpan water system in ancient China.

Waterwheels, turbines, and mills

Hydropower has been used for hundreds of years. In India, water wheels and watermills were built; in Imperial Rome, water powered mills produced flour from grain, and were also used for sawing timber and stone; in China, watermills were widely used since the Han Dynasty. The power of a wave of water released from a tank was used for extraction of metal ores in a method known as hushing. The method was first used at the Dolaucothi gold mine in Wales from 75 AD onwards, but had been developed in Spain at such mines as Las Medulas. Hushing was also widely used in Britain in the Medieval and later periods to extract lead and tin ores. It later evolved into hydraulic mining when used during the California gold rush.

In China and the rest of the Far East, hydraulically operated "pot wheel" pumps raised water into irrigation canals. At the beginning of the Industrial revolution in Britain, water was the main source of power for new inventions such as Richard Arkwright's water frame.[1] Although the use of water power gave way to steam power in many of the larger mills and factories, it was still used during the 18th and 19th centuries for many smaller operations, such as driving the bellows in small blast furnaces (e.g. the Dyfi Furnace)[2] and gristmills, such as those built at Saint Anthony Falls, which uses the 50-foot (15 m) drop in the Mississippi River.

In the 1830s, at the early peak in U.S. canal-building, hydropower provided the energy to transport barge traffic up and down steep hills using inclined plane railroads. About the same time and later, as railroads overtook canals for transportation, canal systems were modified and developed into hydropower systems; the history of Lowell, Massachusetts is a classic example of commercial development and industrialization, built upon the availability of water power.

During this time also, technological advances had moved the water wheel to a turbine, and in 1848 James B. Francis, while working as head engineer of Lowell's Locks and Canals company, improved on these designs to create a turbine with 90% efficiency. Applying scientific principles and testing methods he produced a very efficient turbine design, but more importantly, his mathematical and graphical calculation methods improved turbine design and engineering. His analytical methods allowed confident design of high efficiency turbines to exactly match a site's specific flow conditions. The Francis reaction turbine is still in wide usage today, with few changes in either design or methods. In the 1870s and deriving from uses in the California mining industry, Lester Allan Pelton developed the high efficiency Pelton wheel impulse turbine, which utilized hydropower with very different conditions of flow and pressure.

Hydraulic power-pipe networks

Hydraulic power networks also developed, using pipes to carrying pressurized water and transmit mechanical power from the source to end users elsewhere locally; the power source was normally a head of water, which could also be assisted by a pump. These were extensive in Victorian cities in the United Kingdom. A hydraulic power network was also developed in Geneva, Switzerland. The world famous Jet d'Eau was originally designed as the over-pressure relief valve for the network.[3]

Compressed air hydro

Where there is a plentiful head of water it can be made to generate compressed air directly without moving parts. In these designs, a falling column of water is purposely mixed with air bubbles generated through turbulence at the high level intake. This is allowed to fall down a shaft into a subterranean, high-roofed chamber where the now-compressed air separates from the water and becomes trapped. The height of falling water column maintains compression of the air in the top of the chamber, while an outlet, submerged below the water level in the chamber allows water to flow back to the surface at a slightly lower level than the intake. A separate outlet in the roof of the chamber supplies the compressed air to the surface. A facility on this principal was built on the Montreal River at Ragged Shutes near Cobalt, Ontario in 1910 and supplied 5,000 horsepower to nearby mines.[4]

Modern usage

There are several mature forms of water power currently in wide usage, and other forms which are still in phases of development. Most hydropower is used primarily to generate electricity, but some are purely mechanical. Broad categories include:

Riverine hydropower

- Conventional hydroelectric, referring to hydroelectric dams.

- Run-of-the-river hydroelectricity, which captures the kinetic energy in rivers or streams, without the use of dams.

- Pumped-storage hydroelectricity, to pump up water, and use its head to generate in times of demand.

Marine energy

- Marine current power, which captures the kinetic energy from marine currents.

- Osmotic power, which channels river water into a container separated from sea water by a semi-permeable membrane.

- Ocean thermal energy, which exploits the temperature difference between deep and shallow waters.

- Tidal power, which captures energy from the tides in horizontal direction. Also a popular form of hydroelectric power generation.

- Tidal stream power, usage of stream generators, somewhat similar to that of a wind turbine.

- Tidal barrage power, usage of a tidal dam.

- Dynamic tidal power, utilizing large areas to generate head.

- Wave power, the use ocean surface waves to generate power.

Calculating the amount of available power

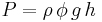

A hydropower resource can be measured according to the amount of available power, or energy per unit time. In large reservoirs, the available power is generally only a function of the hydraulic head and rate of fluid flow. In a reservoir, the head is the height of water in the reservoir relative to its height after discharge. Each unit of water can do an amount of work equal to its weight times the head.

The amount of energy, E, released when an object of mass m drops a height h in a gravitational field of strength g[5] is given by

The energy available to hydroelectric dams is the energy that can be liberated by lowering water in a controlled way. In these situations, the power is related to the mass flow rate.

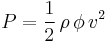

Substituting P for E⁄t and expressing m⁄t in terms of the volume of liquid moved per unit time (the rate of fluid flow, φ) and the density of water, we arrive at the usual form of this expression:

or

A simple formula for approximating electric power production at a hydroelectric plant is:

where P is Power in kilowatts, h is height in meters, r is flow rate in cubic meters per second, g is acceleration due to gravity of 9.8 m/s2, and k is a coefficient of efficiency ranging from 0 to 1. Efficiency is often higher with larger and more modern turbines.[6]

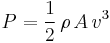

Some hydropower systems such as water wheels can draw power from the flow of a body of water without necessarily changing its height. In this case, the available power is the kinetic energy of the flowing water.

where v is the speed of the water, or with

where A is the area through which the water passes, also

Over-shot water wheels can efficiently capture both types of energy.

See also

References

- ^ Kreis, Steven (2001). "The Origins of the Industrial Revolution in England". The history guide. http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/lecture17a.html. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ Gwynn, Osian. "Dyfi Furnace". BBC Mid Wales History. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/mid/sites/history/pages/dyfifurnace.shtml. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ Jet d'eau (water foutain) on Geneva Tourism

- ^ Maynard, Frank (November 1910). "Five thousand horsepower from air bubbles". Popular Mechanics: Page 633. http://books.google.com/books?id=-N0DAAAAMBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Standard gravity is 9.80665 m/s2

- ^ Donald G. Fink and H. Wayne Beaty, Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers, Eleventh Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1978, ISBN 0-07020974-X pp. 9-3 and 9-4

External links

- International Hydropower Association

- International Centre for Hydropower (ICH) hydropower portal with links to numerous organizations related to hydropower worldwide

- Practical Action (ITDG) a UK charity developing micro-hydro power and giving extensive technical documentation.

- $11 Million Dedicated To Water Power Research.

- Micro-hydro power, Adam Harvey, 2004, Intermediate Technology Development Group, retrieved 1 January 2005 from ITDG.org

- Microhydropower Systems, US Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, 2005

- Allan. April 18, 2008. Undershot Water Wheel. Retrieved from Builditsolar.com

- Shannon, R. 1997. Water Wheel Engineering. Retrieved from Permaculturewest.org.au

|

|||||